Sant Kabir Ji

Al-Kabir (“the Great”) is also one of the 99 names of God in Islam. For a complete disambiguation page, see Kabir (disambiguation)

| Born | 1440 |

|---|---|

| Died | 1518 |

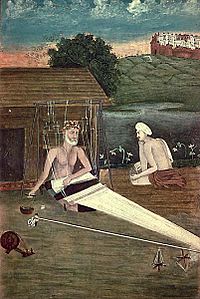

| Occupation | Weaver, poet |

| Known for | influenced the Bhakti movement |

Kabīr (also Kabīra) (Hindi: कबीर, Punjabi: ਕਬੀਰ, Urdu: کبير) (1440–1518)[1] was a mystic poet and saint of India, whose writings have greatly influenced the Bhakti movement. The name Kabir comes from Arabic al-Kabīr which means ‘The Great’ – the 37th name of God in Islam.

Apart from having an important influence on Sikhism, Kabir’s legacy is today carried forward by the Kabir Panth (“Path of Kabir”), a religious community that recognizes him as its founder and is one of the Sant Mat sects. Its members, known as Kabir panthis, are estimated to be around 9,600,000. They are spread over north and central India, as well as dispersed with the Indian diaspora across the world, up from 843,171 in the 1901 census.[2] His writings include Bijak, Sakhi Granth, Kabir Granthawali and Anurag Sagar.[3]

Early life and background

Not much is known of Kabir’s birth parents, but it is known that he was brought up in a family of Muslim weavers. He was found by a Muslim weaver named Niru and his wife, Nima, in Lehartara, situated in Varanasi. They adopted the boy and taught him the weaver’s trade.

The story is told that on one particular day of the year, anyone can become a disciple by having a master speak the name of God over him. It is common for those who live near the Ganges to take their morning bath there in the sacred waters. The bhakti saint Ramananda was in the habit of arising before dawn to take his bath. On this special day too, he awoke before dawn and found his way down to the steps of the Ganges. As he was walking down the steps to the waters, a little hand reached out and grabbed the saint’s big toe. Ramananda was taken by surprise, and he involuntarily called out the name of God. Looking down, he saw in the early morning light the hand of the young Kabir. After his bath, he noticed that on the back of the little one’s hand was written in Arabic the name Kabīr. He adopted him as son and disciple and brought him back to his ashram, much to the consternation of his Hindu students, some of whom left in protest.[citation needed]

Not much is known about what sort of spiritual training Kabir may have received. He did not become a sadhu, nor did he ever abandon worldly life. Kabir chose instead to live the balanced life of a householder and mystic, a tradesman and contemplative.

Kabir’s family is believed to have lived in the locality of Kabir Chaura in Varanasi. Kabīr maṭha (कबीरमठ), a maṭha located in the back alleys of Kabir Chaura, celebrates his life and times. Accompanying the property is a house named Nīrūṭīlā (नीरू टीला) which houses Niru and Nima’s graves.[4] The house also accommodates students and scholars who live there and study Kabir’s work.

Philosophies

Kabir was influenced by the prevailing religious mood of his times, such as old Brahmanic Hinduism, Hindu and Buddhist Tantrism, the teachings of Nath yogis and the personal devotionalism of South India mixed with the imageless God of Islam.[5] The influence of these various doctrines is clearly evident in Kabir’s verses. Eminent historians like R.C. Majumdar, P.N. Chopra, B.N. Puri and M.N. Das have held that Kabir is the first Indian saint to have harmonised Hinduism and Islam by preaching a universal path which both Hindus and Muslims could tread together.[6] But there are a few critics who contest such claims.[5]

The basic religious principles he espoused are simple. According to Kabir, all life is an interplay of two spiritual principles. One is the personal soul (Jivatma) and the other is God (Paramatma). It is Kabir’s view that salvation is the process of bringing these two divine principles into union. The incorporation of much of his verse in Sikh scripture, and the fact that Kabir was a predecessor of Guru Nanak, have led some western scholars to mistakenly describe him as a forerunner of Sikhism.[7]

His greatest work is the Bijak (the “Seedling”), an idea of the fundamental one. This collection of poems elucidates Kabir’s universal view of spirituality. Though his vocabulary is replete with Hindu spiritual concepts, such as Brahman, karma and reincarnation, he vehemently opposed dogmas, both in Hinduism and in Islam. His Hindi was a vernacular, straightforward kind, much like his philosophies. He often advocated leaving aside the Qur’an and Vedas and simply following Sahaja path, or the Simple/Natural Way to oneness in God. He believed in the Vedantic concept of atman, but unlike earlier orthodox Vedantins, he spurned the Hindu societal caste system and murti-pujan (idol worship), showing clear belief in both bhakti and Sufi ideas. The major part of Kabir’s work as a bhagat was collected by the fifth Sikh guru, Guru Arjan Dev, and incorporated into the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib.

Poetry

Kabir composed in a pithy and earthy style, replete with surprise and inventive imagery. His poems resonate with praise for the true guru who reveals the divine through direct experience, and denounce more usual ways of attempting god-union such as chanting, austerities, etc. Kabir, being illiterate, expressed his poems orally in vernacular Hindi, borrowing from various dialects including Avadhi, Braj, and Bhojpuri.[8] His verses often began with some strongly worded insult to get the attention of passers-by. Kabir has enjoyed a revival of popularity over the past half century as arguably the most accessible and understandable of the Indian saints, with a special influence over spiritual traditions such as those of Sant Mat, Garib Das and Radha Soami.[citation needed]

Legacy

A considerable body of poetical work has been attributed to Kabir. And while two of his disciples, Bhāgodās and Dharmadās, did write much of it down, “…there is also much that must have passed, with expected changes and distortions, from mouth to mouth, as part of a well-established oral tradition.”[9]

Poems and songs ascribed to Kabir are available today in several dialects, with varying wordings and spellings as befits an oral tradition. Opinions vary on establishing any given poem’s authenticity.[10] Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the spirit of this mystic comes alive through a “unique forcefulness… vigor of thought and rugged terseness of style.”[11]

Kabir and his followers named his poetic output as ‘bāņīs,’ utterances. These include songs, as above, and couplets, called variously dohe, śalokā (Sanskrit ślokā), or sākhī (Sanskrit sākşī). The latter term, meaning ‘witness,’ best indicates the use that Kabir and his followers envisioned for these poems: “As direct evidence of the Truth, a sākhī is… meant to be memorized… A sākhī is… meant to evoke the highest Truth.” As such, memorizing, reciting, and thus pondering over these utterances constitutes, for Kabir and his followers, a path to spiritual awakening.[12]

Kabir’s poetry today

There are several allusions to Kabir’s poetry in mainstream Indian film music. The title song of the Sufi fusion band Indian Ocean‘s album Jhini is an energetic rendering of Kabir’s famous poem “The intricately woven blanket”, with influences from Indian folk, Sufi traditions and progressive rock.

Documentary filmmaker Shabnam Virmani, from the Kabir Project, has produced a series of documentaries and books tracing Kabir’s philosophy, music and poetry in present day India and Pakistan. The documentaries feature Indian folk singers such as Prahlad Tipanya, Mukhtiyar Ali and the Pakistani Qawwal Fareed Ayaz.

Kabir’s poetry has appeared prominently in filmmaker Anand Gandhi‘s films Right Here Right Now and Continuum.

References

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Westcott, G. H. (2006). Kabir and the Kabir Panth. Read Books. p. 2. ISBN 140671271X. http://books.google.com/?id=FJoX5-hTmVgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Kabir+-inauthor:%22Kabir%22&cd=14#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ Available for download

- ^ http://www.kabirchaura.com/math/math11.htm

- ^ a b The Bijak of Kabir (2002), Linda Beth Hess and Śukadeva Siṃha, Oxford University Press. pp.5 ISBN 0-19-514876-2

- ^ A Social, Cultural and Economic History of India, Volume II, (1974) Macmillan, pp. 90

- ^ Harbans Singh. “Encyclopedia Of Sikhism”. http://www.punjabilok.com/faith/sufi_bhakti/sant_kabir.htm.

- ^ Scudiere, Todd. “Rare Literary Gems: The Works of Kabir and Premchand at CRL”. South Asian Studies, Spring 2005 Vol. 24, Num. 3. Center for Research Libraries. http://www.crl.edu/focus/article/510.

- ^ The Vision of Kabir: Love poems of a 15th Century Weaver, (1984) Alpha & Omega, pp. 47 ASIN: B000ILEY3U

- ^ The Vision of Kabir: Love poems of a 15th Century Weaver, (1984) Alpha & Omega, pp. 49-51 ASIN: B000ILEY3U

- ^ The Vision of Kabir: Love poems of a 15th Century Weaver, (1984) Alpha & Omega, page 55 ASIN: B000ILEY3U

- ^ The Vision of Kabir: Love poems of a 15th Century Weaver, (1984) Alpha & Omega, page 48 ASIN: B000ILEY3U

Further reading

- Bly, Robert, tr. Kabir: Ecstatic Poems. Beacon Press, 2004. (ISBN 0-8070-6384-3)

- Dass, Nirmal, tr. Songs of Kabir from the Adi Granth. SUNY Press, 1991. (ISBN 0-7914-0560-5)

- Kabir. Compilation of Kabir’s dohas in Devanagiri. Kabir ke dohey

- Masterman, David, ed/rev. Kabir says… Los Angeles: Three Pigeons Publishing, 2011.

- Tagore, Rabindranath, tr. Songs of Kabir. Forgotten Books, 1985. (ISBN 1-60506-643-5) Songs of Kabir

- Vaudeville, Charlotte. A Weaver Named Kabir: Selected Verses with a Detailed Biographical and Historical Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. (ISBN 0-19-563933-2)

- KavitaKosh.org Compilation of Kabir’s dohas in Devanagiri Kabir Page on Kavitakosh